|

Previous Issues |

| Cedar Mill Community Website |

|

Search the Cedar Mill News: |

About The Cedar Mill News |

|

|||||||

| Volume 15, Issue 1 | January 2017 |

||||||

The Nature of Cedar Mill

|

|||||

|

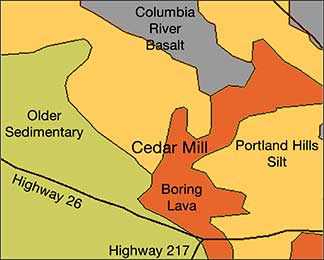

The underlying rock in our area is Columbia River Basalt. This was laid down by enormous lava flows from volcanoes near the Oregon-Washington-Idaho border around 14-16 million years ago. At this time, there were no intervening mountains to slow the flow, which finally solidified here after a trip of some 350 miles. The Cascades were created later!

Our dark grey basalt was relatively cool when it reached the area, and is fairly soft and deteriorates into smaller rocks and clay. In Bonny Slope there are only a few feet of soil above the basalt bedrock, as many a developer has discovered. A lot of the topsoil is simply dust blown up from the Tualatin Valley, a process that continues today as tidy housekeepers have discovered!

This area is also full of springs resulting from groundwater escaping through cracks in the basalt. Many houses in the area need sump pumps in the basement to remove the seepage. Recent comments on NextDoor refer to a spring that is causing a small “glacier” in a Bonny Slope neighborhood!

Most of the landscape features in the Willamette Basin were formed by compression resulting from the Pacific plate diving under the continental plate during the last 5 million years. This caused “downwarping and uplifting,” resulting in hills and basins. The Tualatin Hills that form our northeastern margin are part of an “anticline,” which is a curving formation of uplifted terrain.

The layer of soil in areas above 350 ft. is “loess,” windblown silt formally called Portland Hills Silt. It is anywhere from six inches to 150 feet thick, and was blown off of the flood plains below.

|

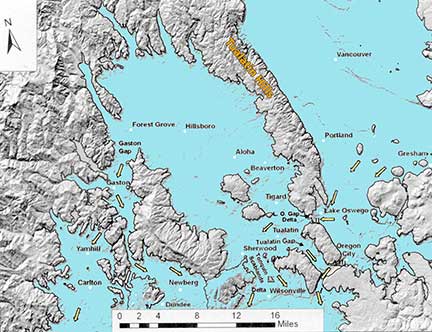

| Flooding in the Tualatin Valley: floodwaters entered mainly at the Lake Oswego Gap and exited at the Tonquin Scablands, the Tualatin Gap, and the Gaston Gap. Used with permission from "Cataclysyms on the Columbia." |

Below 350 ft are the Missoula Flood sediments that are dominated by silts and sands. The mineralogy is the same as the loess (which was originally the Missoula Flood silts that blew uphill). The Missoula Floods were a series of some 40 floods that occurred around 15,000-18,000 years ago. During the end of that ice age, ice dams in the area that is now Montana ruptured repeatedly.

Each time an ice dam ruptured, vast amounts of water rushed down the Columbia basin, widening and deepening the Columbia Gorge and forming many of the landscape features we are familiar with. Water entered the Tualatin Valley near what is now Lake Oswego. The silt left behind was distributed by wind to cover the bedrock around the valley. It’s estimated that the water filled what is now the Tualatin basin for several weeks after each flood.

Probably the most interesting feature of Cedar Mill geology is the existence of lava tubes near our eastern areas. These were formed by the eruptions of three small volcanoes, located near where Highway 26 goes into the tunnel. One of these volcanoes is called Elk Point—the others are unnamed. They are relatively young, having formed approximately 244,000 years ago. These light grey lava flows are known as Boring Lava, not for their lack of interest, but because it was first identified near Boring, Oregon.

A lava tube is a tunnel formed when the surface of a lava flow cools and solidifies while the still-molten interior flows through and drains away. One of these lava tubes was found during excavation for St. Vincent’s Hospital in the late ‘60s. It took 6000 truckloads of concrete to fill up the collapsed lava tube to create a stable foundation for the hospital.

Gardeners in the area have reported feeling cold air coming out of the ground from cracks in a lava tube. There are several other tubes that open to the surface, but all are on private property.

For more information on local geology, visit the library for a copy of Geology of Oregon, by Elizabeth Orr. Scott Burns has recently released the revised second edition of his book, “Cataclysms on the Columbia: The Great Missoula Floods,” available on Amazon. If you ever get the chance to attend one of his presentations, you’ll enjoy his lighthearted approach to the material he knows so well. Who knew geology could be so funny?

![]()

Like us on Facebook for timely updates

Published monthly by Pioneer Marketing & Design

Publisher/Editor:Virginia Bruce

info@cedarmillnews.com

PO Box 91061

Portland, Oregon 97291

© 2017