|

Previous Issues |

| Cedar Mill Community Website |

|

Search the Cedar Mill News: |

About The Cedar Mill News |

|

|||||||

| Volume 13, Issue 12 | December 2015 |

||||||

Lasagna garden!

|

|||

|

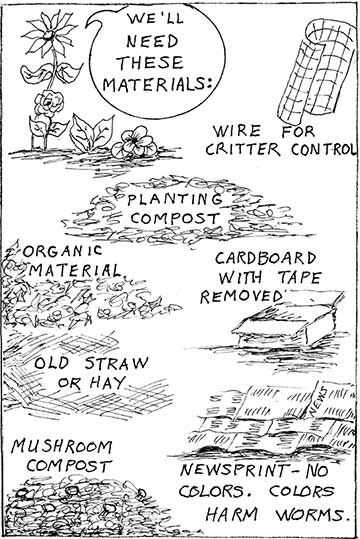

Nelson says, “Using the “lasagna” method (think layers), you can actually compost directly on your garden or raised bed. You build compost layers of “green” material (high in nitrogen, such as vegetable scraps, coffee grounds, or chicken manure) and “brown” material (high in carbon, such as leaves, straw, or newspaper) right on top of the soil. As you add layers to the pile, the layers below will continue to compost.”

I started by laying down some large pieces of cardboard I had collected. You can also use newspapers, but I have found that some tenacious weeds work their way through even several layers of newspaper–plus it can be hard to separate out the colored pages which contain metal that our worms and other “decomposers” don’t like. Appliance stores are usually happy to let you have as many as you need.

Then I spread about a three-inch layer of wood chips, which Badger left for me after chipping up the branches from my tree. They and other tree services are often happy to drop off large piles of this valuable material for free. This helps hold down the cardboard once winter storms set in. It’s great for making paths, too. While it decomposes slowly, in a few years you’ll never know it was there.

I added some straw I happened to have, along with some dried up piles of weeds from all around my place, and then covered the whole thing with used-up soil from some large garden bins I had been using for many years. The soil wasn’t fertile any more, but it would be a good planting medium and plant roots would find their way to the decomposing compost-y levels below. You can get compost or top soil delivered from Cedar Mill Landscape Supply and other companies to make that layer.

Nelson says, “Covering the bed with its compost pile loosely in plastic may help speed decomposition during colder months, and will prevent rain from washing valuable nutrients out of the compost and into the stormwater system. You do not need to turn this type of compost pile, and if the composting process is complete, you should not even need to till before planting.” The no-till method is ancient, but it’s also the latest thing in sustainable permaculture-type gardening practices.

Depending on the rate of composting, Nelson says, “The result is often ready-to-plant composted beds in the spring. If the composting is slow, though, it may take a full year for the material to fully compost. It may be a good idea to plan for a rotation between two beds to allow two full years for the pile to compost.”

In my case, I planted shallow-rooting crops the first year, such as strawberries, radishes, and lettuce. I was able to plant almost anything the second year, and created new beds to fill up the rest of the available space.

Ready to learn more? Visit Oregon State University Extension’s Polk County Master Gardeners online for the entertaining how-to illustrated guide.

![]()

Like us on Facebook for timely updates

Published monthly by Pioneer Marketing & Design

Publisher/Editor:Virginia Bruce

info@cedarmillnews.com

PO Box 91061

Portland, Oregon 97291

© 2015