Last month we covered the basics of good soil structure. This month we are focusing on several methods to achieve this—polyculture, cover-cropping, and crop rotation.

Permaculture is about whole systems thinking, so we view the Soil Food Web as a living whole, composed of innumerable parts, which is also part of a much larger whole—the Web of Life—an amazing variety of habitats, people, plants, and animals all interconnected in the fragile entity we call “biodiversity.” Every member is essential to keeping this web in balance.

When we begin to see soil as a living entity that can die or be killed, we realize that the true purpose of soil conservation is to keep soil alive, healthy and vigorous. To conserve is to enable to function. Healthy living soil function means the well-being, in full creative activity, of each of its parts in harmony with every other part and also with the whole system.

Keeping your soil alive

Soil conservation is the remedy for, and the prevention of, soil erosion—which is the end result of a sick and dying soil. The first symptom of this is the loss of soil structure. As we learned last month, soil structure relates to the size of soil particles. This means that there is enough air space between them so that the soil organisms and plant roots can breathe and water can move. When this conductivity is disrupted, a hard insulating layer, or pan, develops.

The destructive process that ends in soil erosion begins with the loss of surface vegetation. This is caused by over-grazing on pasture land, and by over-cultivation without proper conserving rotations and the return of sufficient organic matter to arable land. If this process of mismanagement continues, the humus in the soil is rapidly used up. Since humus is both the food and habitat of soil life, it follows that, as it becomes depleted, the soil life begins to die. The sponge-like character of fertile soil is created and maintained by soil organisms in the process of living, so when they die, the soil begins to lose its cohesion and stability, and then it loses its structure. It then runs together after a rain, which immediately interferes with the air supply and seals its surface. When the hot sun hits that wet surface, it bakes. Then the next rain, instead of penetrating, runs off, carrying top soil with it; or in dry times, it cracks and the surface turns to dust and blows away.

In other words, it entirely alters its character from living soil of good structure, which can receive and use the elements—wind, water, and sunlight— for its benefit, to a conglomerate, inert, unstable mass for which the once life-giving sun and rain have become its worst enemies, bringing about the next stage in the downward progression to total erosion, which is the physical removal of all of the topsoil, with the minerals that plants need being leached out.

With our whole-systems understanding of soil we can begin to talk about how we can use permaculture methods to facilitate and build a healthy soil ecosystem. The practice of sheet mulching, which I wrote about in the April issue, enhances and builds soil without disturbing the existing natural system. By adding organic matter and mulch in layers, we are ensuring that our natural allies— mycelia, worms, microorganisms, and bacteria— have something to break down and turn into rich topsoil, full of humus. With this practice, there is rarely a need to add any additional fertilizers.

With our whole-systems understanding of soil we can begin to talk about how we can use permaculture methods to facilitate and build a healthy soil ecosystem. The practice of sheet mulching, which I wrote about in the April issue, enhances and builds soil without disturbing the existing natural system. By adding organic matter and mulch in layers, we are ensuring that our natural allies— mycelia, worms, microorganisms, and bacteria— have something to break down and turn into rich topsoil, full of humus. With this practice, there is rarely a need to add any additional fertilizers.

This is a good example of the permaculture principal of working with, rather than against natural systems. When you work with a system, by nourishing and enhancing its processes, the system is balanced and therefore thrives and is productive. When you work against a natural system, by over-tilling and monocropping, for example, the system is thrown out of balance, requiring outside energy inputs in the form of fertilizers and pesticides, in order for it to remain productive.

Perennial polyculture

By adding perennial polyculture methods (the inter-planting of two or more species) we are creating a full natural systems habitat. Perennials, unlike annuals, produce flowers and seeds more than once in their lifetime, and therefore do not have to be planted every year. This is how nature works, and in permaculture we not only desire to work with natural systems, we work to mimic them.

In the annual vegetable garden we can use these methods, altering them to the needs of this type of production. We do this by seasonally adding layers to the sheet mulch, inter-planting plant allies (companion planting), practicing crop rotation, and cover cropping.

Cover crops and crop rotation

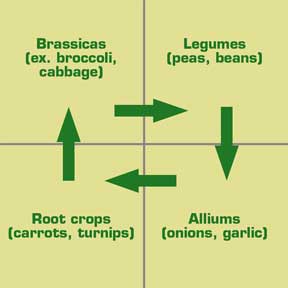

Cover cropping prevents disease and pest insects and increases soil fertility. Crop plants that are in the same plant families tend to share the same insect and disease problems. When we grow plants from the same families in the same place year after year, disease organism and pest insect populations build up and accumulate in the soil, leading to ecosystem imbalance. It is recommended that you wait three to seven years between growing crops from the same family in the same place in order to maintain a healthy balance.

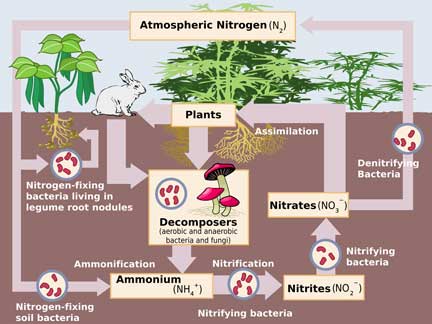

Crop rotation for the purpose of soil fertility minimizes the need to add fertilizers. This is because different plants extract soil nutrients at different rates. Nitrogen tends to be used up or leached out relatively quickly, while phosphorus, potassium, calcium and trace minerals will remain in healthy soil in adequate amounts for a few seasons. Because of this, the main reason we need to apply additional fertilizers is to replace nitrogen. By rotating nitrogen-fixing plants throughout the garden, such as alfalfa, clover, fava beans, peas, and lupines, we can harness the nitrogen cycle to replace nitrogen in the soil. Nitrogen-fixing plants have nodules on their roots that are actually large colonies of bacteria. These bacteria use nitrogen gas from the air and transform it into forms that are useful to plants. For more information about plant families and crop rotation techniques download this PDF file.

Crop rotation for the purpose of soil fertility minimizes the need to add fertilizers. This is because different plants extract soil nutrients at different rates. Nitrogen tends to be used up or leached out relatively quickly, while phosphorus, potassium, calcium and trace minerals will remain in healthy soil in adequate amounts for a few seasons. Because of this, the main reason we need to apply additional fertilizers is to replace nitrogen. By rotating nitrogen-fixing plants throughout the garden, such as alfalfa, clover, fava beans, peas, and lupines, we can harness the nitrogen cycle to replace nitrogen in the soil. Nitrogen-fixing plants have nodules on their roots that are actually large colonies of bacteria. These bacteria use nitrogen gas from the air and transform it into forms that are useful to plants. For more information about plant families and crop rotation techniques download this PDF file.

Cover cropping increases nutrients, adds organic matter to the soil, helps to suppress weeds and provides catch crops and forage crops, A catch crop is a cover crop established after harvesting the main crop and is used primarily to reduce nutrient leaching from the soil. For example, planting cereal rye following corn harvest helps to scavenge residual nitrogen. Short-rotation forage crops function both as cover crops, and as green manures when they are eventually incorporated or killed for a no-till mulch. Examples include legumes such as alfalfa, and clover, as well as grasses like fescue. In general practice, cover crops are tilled into the soil, but in the case of adding to the sheet mulching process they are cut down and laid on top of the mulch, adding a layer of green manure. Some other useful plants for cover cropping include; fava beans, bush beans, buckwheat, rye grass, and vetch.

Using these techniques in a home garden may sound daunting, but with a little planning and attention to the long-term health of your soil, you’ll be rewarded with healthy crops and remarkably pest and disease-free plots.