Protect and build your soil!

By Dean Moberg

What is your dirt?

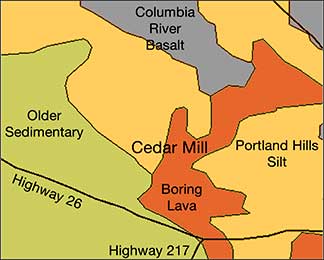

Most soils in the Cedar Mill area formed in material deposited 13,000 to 15,000 years ago during the last part of the ice age. The remarkable “Missoula Floods” of that time, described in the book Cataclysms on the Columbia (Allen et al., 2009), explains how these soil-forming materials arrived.

Soils below about 300 feet in elevation, for example around Sunset High School, mostly originated with sediments from a deep lake that the Missoula Floods formed over much of what is now Washington County. The sediments developed into fertile soils, which often have about 5-10 inches of silt loam topsoil overlying a silty clay loam subsoil and are suitable for a wide variety of crops.

Soils above around 400 feet, for example between Mill Pond and Skyline Blvd., were not underwater during the Missoula flood events. These soils formed from silt (dust) blown by wind from east of the Cascade Mountains. They have a silt loam topsoil and subsoil and grow productive forests, with Douglas fir trees reaching over 100 feet tall in 50 years.

Soils at elevations of roughly 300 to 400 feet are hybrids, forming from wind-blown silt that covered up the highest Missoula Flood deposits. These soils are fertile and suited to a variety of crops. They have a silt loam topsoil and a subsoil with some silty clay loam.

In some of our subdivisions, developers scraped away the topsoil by grading. If that’s your situation, loads of mulch, compost, cover crops, and patience can build soil.

Build your soil!

Regardless of soil type, there are three springtime tips for making soil healthier and more productive. Healthy soil is a complex ecosystem with a diversity of life, including roots, earthworms, bacteria, fungi, nematodes, tardigrades, and other fascinating creatures living out their lives in the dark loam. Just as we protect rainforest or coral reef ecosystems, we make soil ecosystems healthier by protecting the soil organisms and their habitat.

First, don’t leave bare soil exposed to the driving force of rain or the devastating heat of the sun. Instead, apply a thin 1-2-inch layer of compost around plants. Compost insulates soil from temperature extremes, holds soil moisture, and feeds a healthy ecosystem. You can buy compost at garden stores or make your own. Washington State University has a Backyard Composting publication available free online.

Second, minimize soil disturbance. Rototilling is terrible for soil—it kills many beneficial organisms outright and destroys the habitat other soil creatures need. Rather than rototilling or aggressively digging up your garden, try digging only the small hole needed for a vegetable or flower transplant. Or dig a shallow trench for seeds that you then cover lightly with soil and a dusting of compost.

Third, minimize the use of harsh chemicals such as conventional fertilizers and pesticides. These products may not harm plants directly but can be toxic to a healthy soil ecosystem. Try using natural fertilizers like feather meal and hand-pulling or using shallow hoeing to control weeds.

The Cedar Mill Library has gardening books with soil care information. The Tualatin Soil and Water Conservation District website lists free educational activities with practical information about soil health, water conservation, wildlife habitat, pollinators, and more.

Dean is a director on the Tualatin Soil and Water Conservation District Board. He recently retired after a 35-year career with the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Dean and his family have lived in Cedar Mill since 1995. Contact Dean at 503-720-9024 or deanpmoberg@gmail.com