BSD planning and the upcoming Bond Measure

By Vicky Siah

The Beaverton School District (BSD) capital improvement bond will appear on the upcoming May 2022 ballot. If passed, this 30-year plan would raise more funds for BSD to renovate buildings, add learning spaces, improve accessibility, and replace student technology. According to the BSD website, this would increase the current estimated Year 1 average tax ($633) to $709 for an average assessed property value of $303,021. If this bond does not pass, the estimated Year 1 average tax would be lowered to $509 (a decrease of $124).

About the bond

On May 14, 2021, BSD released their Long-Range Facility Plan (LRFP) on the district website. This plan included facility condition surveys, population metrics, and educational program evaluations. Through this, BSD identified areas that should be improved on, including:

- An extra gym for Stoller Middle School

- Rebuilding Beaverton High School

- Rebuilding Raleigh Hills K-8

- Additional portables at Westview High School

- Addressing seismic conditions at 11 schools

- Fixing window moisture and chipped bricks (various schools)

- Improving school aesthetics

These issues pose long-term concerns for BSD, and the district’s bond proposal is meant to address these needs—an estimated $722.6 million bond that will cover all improvements.

Administrators from BSD’s central office have voiced their support for the bond, and in particular, Superintendent Don Grotting discussed this with the Cedar Mill News (CMN). “When buildings drop below standards, they need to be replaced or renovated,” Grotting said.

Shellie Bailey-Shah, BSD’s Public Communications Officer, made similar statements. “In areas where enrollment is consistent, the proposed bond includes projects to add capacity…the district strives to provide a comprehensive and equitable educational experience to all students. This can be achieved in multiple ways by providing equitable opportunities for educational programming and experiences. Funding and staffing of schools are based on enrollment, so that students in one school will have as common an educational experience as students in another school.”

Grotting directed CMN to Chief Facilities Officer Joshua Gamez, but per Gamez and Bailey-Shah, Gamez was unavailable for comment.

Community discourse

The bond proposal sparked deep community discourse on social media, with both sides voicing strong opinions. One community member, who prefers to remain anonymous, cited personal financial obligations as a reason for her “no” vote. “The schools demand too much money as it is. Constantly. I’m still paying back my own educational debts and will be for many more years. I would rather use any extra money to pay down my own student loans,” she wrote. “I want and need my [property] taxes to go down. Those kids can make do with the [Chromebook laptops] and tablets they have now, and the facilities can budget or use the money better. Or the parents can raise their own money for their own schools.”

Another community member stated that “[she has] experienced the benefits of two school bonds as a teacher and parent.” However, she argues that BSD’s success is limited by local property developments and the future strain they will cause on schools. “I also have seen [firsthand] how affected school administrators and district folk have not had any real say in when and where big housing developments occur, even when they have to legally weigh in.”

For several years, in the required response to proposed developments (the Provider Letter), BSD has submitted a “boilerplate” letter that says they will have capacity to serve the resulting student population growth without being specific or referring to already-overcrowded schools. Oregon law does not allow school capacity to prevent development. BSD’s response has been to alter school boundaries and send kids off on buses to attend less crowded schools far from their neighborhoods.

Many community members have been dismayed to watch our education system become more corporate. Consolidation for greater efficiency, including the liberal use of busing, causes lack of sleep from early bus times and eliminates neighborhood friend networks. This has been a consistent policy at BSD. Kids aren’t widgets, and this lack of sensitivity to family and community needs may not be the best use of funds. Is it time to examine the values of potential school board candidates?

Those who are pro-bond cite the importance of education, pay-it-forward mentality, and student necessity as reasons for their support. They believe that funding is needed to bring up Oregon’s high school graduation rate, and that the community’s long-term changes will increase financial demands. Still, some interviewees point out how BSD’s structural flaws have turned them against the bond. “Throwing money at BSD doesn’t solve anything. I’ve seen so much wastage [of funds] in the schools. Do they really need a touchscreen table to play chess in the library? I asked admin, and those were bought with bond funds. How about the package of land they bought east of Westview High? It’s too small to be developed as a middle school, and just big enough for an elementary… but Rock Creek [Elementary] is right across the street. And they say it’s ‘less desirable because of access constraints.’ The problem isn’t the money. It’s that the administration doesn’t know how to spend it. Why would I give my money to a district that will waste it and ask for more at the next bond proposal?”

A former BSD student commented that “over the last few years, BSD really got worse. They spent their money on things that were never used, and it doesn’t make sense to give them more money. It’s like rewarding them for wasting money… with more money.”

Related issues

The proposal also raised questions regarding issues that the LRFP failed to address. One of the most prominent topics revolved around population growth and the area north of Highway 26. Currently, schools north of 26 experience overcrowding (for example, Stoller Middle School), and CPO 7 Chair Mary Manseau sees this as a major issue. “What are the barriers to providing an adequate number of neighborhood schools north of 26?” Manseau asked.

To this, Bailey-Shah responded that “ district planning demonstrates that an adequate number of schools and capacity therein exists north of Highway 26 to support the student enrollment in that area. If the long-term population forecast indicated significant enrollment growth, the district does possess property north of Highway 26 on which schools can be constructed.”

Grotting elaborated by referring to the County’s declining enrollment rates. “The population is projected to decrease in the next few years, according to Washington County birth metrics,” Grotting explained. “We’re paying close attention to the demographics, and new data shows that the enrollment will decrease. Crowding north of 26 will not be as large an issue.”

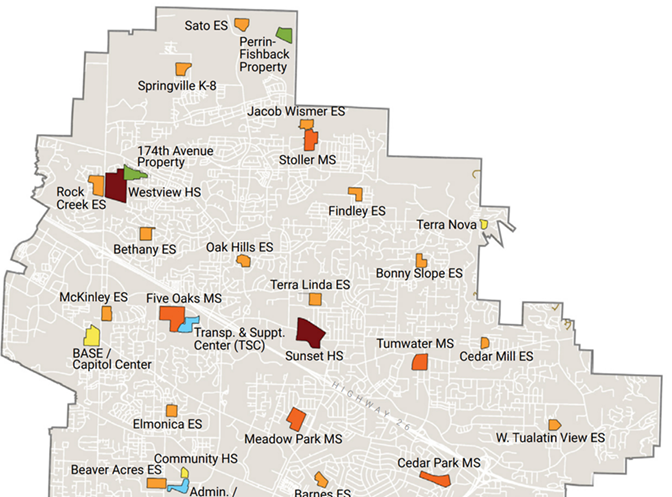

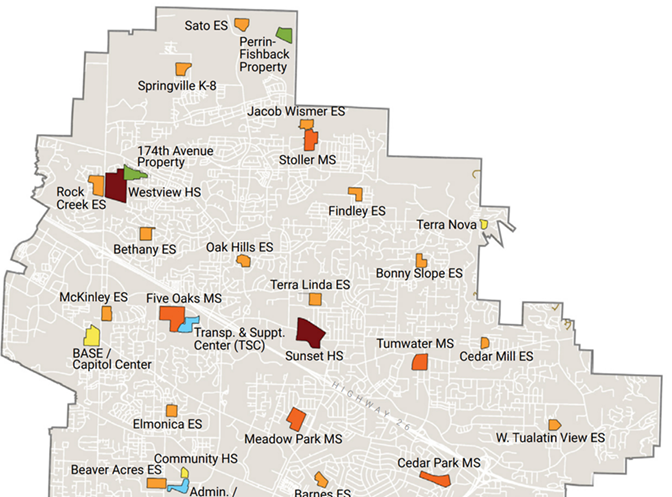

Manseau and many other residents are dissatisfied with these responses, arguing that population trends may change. “In the late 1980s, when my son was just reaching elementary school age, BSD sold off the only middle school site they owned north of 26, and a conversation about whether BSD was going to mothball Oak Hills Elementary School was ongoing. A little over 30 years later, we have two middle schools, Oak Hills is needing to expand, and we have five new elementary schools to serve the exploding residential population north of 26,” Manseau said. As of now, BSD’s LRFP shows two empty sites in the northern region—the 174th Avenue site east of Westview High School and the Perrin-Fishback site (near Springville Road and the northeast boundary of the district–see map). The LRFP notes that the 174th site is not easily accessed from the main road (making it “less desirable”), and the Perrin-Fishback site is only 10 acres (elementary school size) and is quite near Sato Elementary.

The same population trends propelled BSD’s Futures Study. BSD created five approaches to school assignments. Consolidation and busing are a common theme, and Grotting indicated that these are long-term strategies. “Consolidation and busing is a long-term plan as the district decreases population and schools can be shut down. All options [in the document] are on the table,” he added. “I’m aware that construction will lead to more inequity, like how Mountainside is better than Sunset… we’re taking into account environmental impacts, traffic, low incomes, and reduced lunch plans. But what’s best overall may not be good for individual families.”

Grotting remarked that BSD wants the public to be involved in decisions, referencing open-houses, polls, and other forms of community outreach. “We just finished a poll that reached 500-600 people,” he said. “And we’ve been talking to people since last year with our BSD open-houses.”

Calculate your tax impact

Cedar Mill News has created a spreadsheet for readers to calculate their personal financial impacts of each BSD bond option. To use it, log in with your Google account and make a copy of the form.

As we approach the election season, BSD representatives have reached out to CPO 1 and we have invited them to speak about the bond measure as part of the April 12 CPO 1 meeting. Bailey-Shah encourages residents to visit the district’s bond website, where they can peruse district videos, a cost breakdown, and a bond FAQ. The 2021 LRFP can be found on the BSD long-range planning page.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.